The real secrets of the Bohnice cemetery (something to rightly ponder)

In 1909, on 12th September, the new cemetery was consecrated by the worthy lord, Mr. Josef Mejsnar, the Prince Vicar and parish priest of Klecany, with the assistance of the parish priest Josef Sobotka, the director and administrator of the institute, as well as the officials and the sick took part in the ceremony. The first person buried was the inmate Frantisek, a boy of 11 years of age.

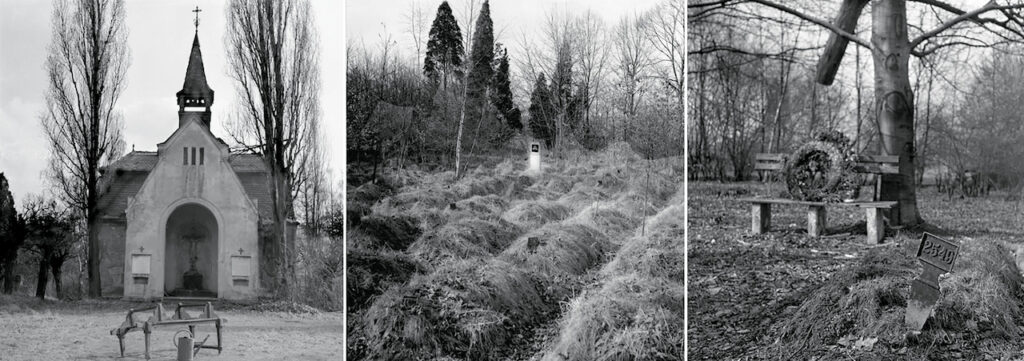

Bohnice Inpatient Cemetery (sometimes referred to as the „Cemetery of Fools“) is a former cemetery located in the northern part of Prague, 700 metres west of the Psychiatric Hospital in Bohnice. The cemetery has an area of about 2.5 ha and is entered through two gates (the main one from the east and a secondary, permanently locked one from the west). There are approximately 4200 graves in total.

The cemetery was completed and consecrated on 12 September 1909 as part of the Psychiatric Hospital in Bohnice. About 80 patients who died in the hospital were buried here annually. In 1951, burials ceased here and the church and the institutional clergy were closed down at the same time. On 1 January 1963 the cemetery was handed over to the Funeral Service of the capital city. Prague. The latter did not use it and left it in disrepair. The cemetery is dominated by a chapel with a mortuary and a cairn built in memory of the soldiers and victims of the First World War who died during their hospitalization in the institute.

The many false rumours can certainly be passed over with a wave of the hand, referring to the eternally vivid human imagination. But the Bohnice institutional cemetery also offers mysteries that are, or probably could be, based on reality. These cannot be dismissed so easily and therefore, unlike the previous tales, we will dwell on them in more detail.

The mysterious tombstone of the mysterious woman

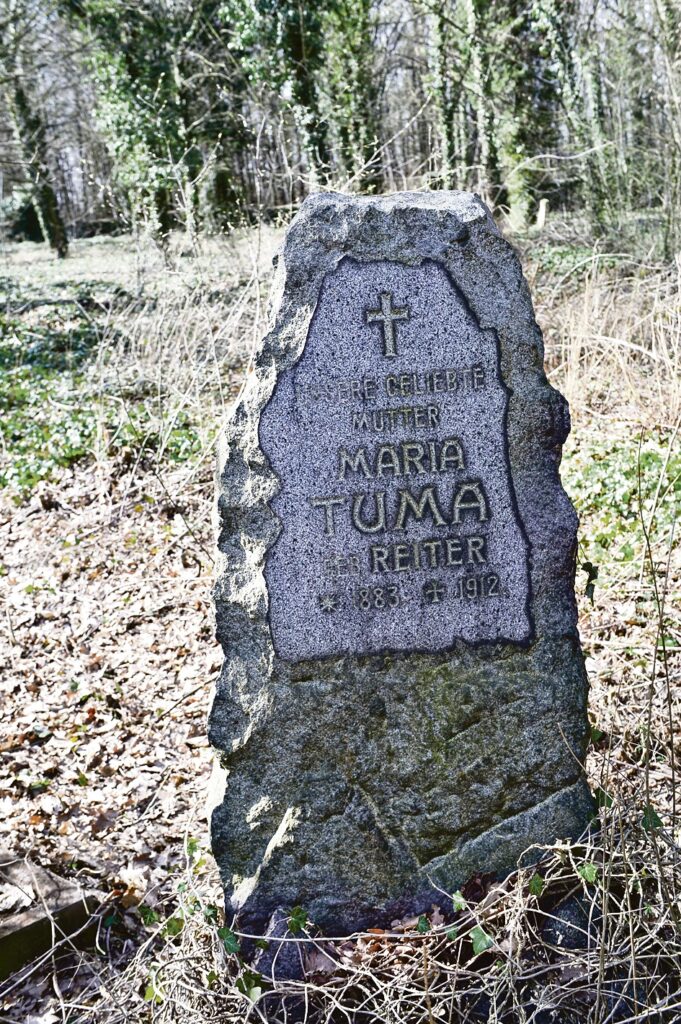

After years of decay, most of the graves in the Bohemian cemetery lack any tombstones. Then there are quite a few tombstones that are dingy, overgrown and illegible. With a bit of luck, we may come across those where the names and dates can be read. However, there has been a single one here for a hundred and seven years that looks like it has been regularly maintained and all the information on it can be read without any problems. The cemetery stone marks the final resting place of a young woman whose name, according to tradition, should not be pronounced. I have respect for tradition, but writing it down is not the same as saying it. So – it is the grave of Maria Tuma Reiter, who died in April 1912, aged just twenty-nine. Her intact tombstone provokes questions. Who was Maria Tuma Reiter anyway?

We don’t know much about her. She was born in Styria, Austria, from where she came to Prague. When she was twenty-three, she married a Czech metalworker, Antonín Tuma. Together they had two children and probably lived quite a happy life. Maria worked as a nanny and maid for a wealthy family until the end of her life. Although even in serious documents and articles it is often stated that she died of „brain decline“, this is not the case. The Book of the Dead clearly speaks of pneumonia, with the footnote „died suddenly“. This brain loss, atrophia cerebri in Latin, is listed as the cause of death in the death certificate for many patients, but not in the case of Maria Tuma Reiter. And although the place of her death is the „Royal Czech Institute for the Insane in Bohnice“, all the evidence suggests that she was not a patient. She probably lived in the „Bohnice colony“. I can’t imagine a family – a wealthy one at that – allowing a woman with symptoms of mental illness into their home and with their children.

The strange Maria Tuma Reiter nevertheless hides one big question mark connected with her person. Who and why maintained her grave for so many years, and how is it possible that it survived the decades of decay unscathed? In recent years, the tombstone has been maintained by the aforementioned Mysterious Places association, and unorganized visitors to the cemetery have also helped by, among other things, bringing candles and other mementos to Mary’s grave. I must also give a thumbs-up to the spiritists in this respect, although I view their alleged communication with the dead Mary – to put it mildly – very critically. If they are „talking“ to her, I wonder if she speaks German, as German was the young woman’s native and main language. Well, I had to blush, but no hard feelings.

Everyone has a hobby.

But this care, covering a relatively short period, cannot be the answer to the whole question. Sure, let’s assume Maria Tuma Reiter had a loving husband. I looked up Antonin Tuma in the list of World War I dead in the Military Central Archives. He’s not there, so we can assume he survived the Great War. So he may have tended the grave for many years, as did his children. After all, the inscription „Unsere geliebte Mutter“ (our beloved mother) on Maria’s stone might suggest a strong relationship between her and her children.

Okay. But we still need to clarify the several decades when neither Antonín Tůma nor his offspring lived.

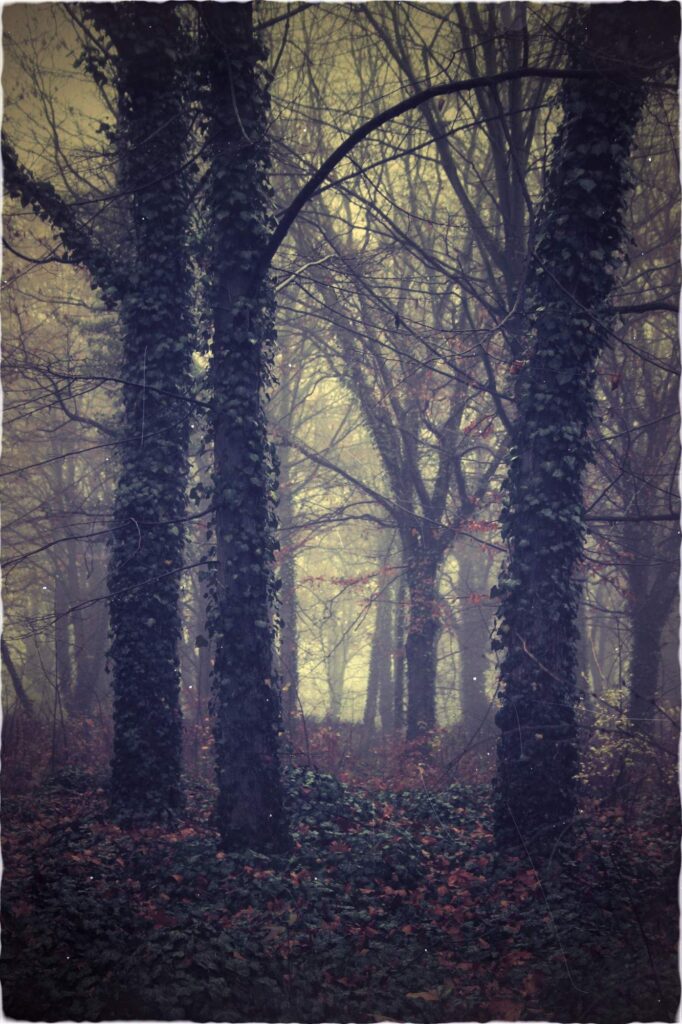

This is a critical period. Just imagine – the cemetery is officially non-existent, overgrown with ivy, weeds and God knows what else. It’s already unknown, almost forgotten. Bags of rubbish are piled up behind the walls, metal thieves occasionally loot it, Satanists appear with their rituals, maybe even vandals. And it’s in these conditions that someone regularly comes here to maintain a grave. We know it can’t be a husband or children anymore. And yet, someone has a really strong motivation, and maybe it’s not one person, but several people. Who? Why? Relatives still in Austria? Hardly. Anyone from the families Maria worked for? Maybe.

Karl Chotezovsky? Gavrilo Princip?

The second mystery of the Bohnice cemetery looks bizarrely impossible at first glance. One of the graves without a headstone is supposed to hide the Serbian assassin Gavrilo Princip. A young student who in the summer of 1914 killed the Austrian-Hungarian heir to the throne and his wife (he did not want to kill her) with shots from a Browning M1910 pistol of 7.65 millimetres. An idealistic Serbian patriot whose shots served as an excuse for the failed Austrian anti-Serbian campaign that led to World War I.

Due to his young age, Princip could not be sentenced to death, but the court gave him the maximum sentence of twenty years in prison. To carry it out, he was assigned to the fortress prison in Terezín, Bohemia. The ailing Princip was kept in terrible conditions until he died of tuberculosis on April 28, 1918.

According to the original version, after the war he was exhumed from an anonymous mass grave in Terezín and transported to Sarajevo in the then Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (today in Bosnia and Herzegovina). But…

Princip’s Terezin exhumation itself stood on a somewhat confusing basis. His body was marked only by one of the prisoners, who allegedly knew where his Austrian captors had buried their victim. Nothing more. But there was no reason to be suspicious then.

It is only with the passage of years that the first testimonies and vague records of the strange burial, which was to take place in the constitutional cemetery in Bohnice just two days after Princip’s death in Terezín, appear. They speak of a nighttime visit by a military escort from the Terezín fortress, with whose assistance an unknown body was lowered into an unmarked grave.

In September 1942, the Gestapo broke up a group of Bohnice hospital workers who were involved in resistance activities. At the interrogation, the departmental undertaker Slavata, among other things, confirmed the unusual burial on May 1, 1918, and stated that the unknown was entered in the Book of the Dead as Karel Chotěžovský. I have indeed found a person of that name in the Book of the Dead, and the time dating is also consistent. Chotěžovský was supposedly a demobilized corporal (corporal) of the 28th Infantry Regiment who, after retiring to civilian life, made his living as a painter. According to the record, he died in a hospital in Bohnice from the proverbial „brain loss“.

Marek Skřipský

Italians in the cemetery

The sad fate of the Italian refugees buried in the Bohnice cemetery.

The former cemetery of the Bohnice psychiatric hospital, popularly known as the cemetery of fools, has been unused for years and until now seemed to be completely forgotten. Recently it has become unusually busy, with amateur paranormal hunters, professional mystery researchers and even Italian historians taking an interest.

BOOK OF THE DEAD 1916-1917 LIBRO DEI MORTI 1916-1917

Tombstones are missing, stolen by thieves, the roofless chapel is perhaps only held together by God’s will. Only the ivy-covered lumps of earth are visible, indicating where the graves lie. The cemetery has recently attracted the interest of the Military History Museum in Rovetero, Trentino, Italy, in connection with the First World War.

In fact, the cemetery is where the patients of the medical hospital in Pergine Valsugana, Italy, which had to be hastily evacuated in March 1916, are buried. More than a hundred patients were hospitalized in Bohnice. But only 46 returned after the war.

According to historians, the evacuation of the hospital in Pergine was only a short episode in a larger story. After the outbreak of the First World War, more than 70,000 inhabitants were evacuated from the northern Italian region of Trentino. As this territory belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the front lines were to run here, the Italian evacuees were distributed in small groups throughout the empire, but mostly in Bohemian and Moravian villages. In May 1915 the evacuation order was issued. They were told to report to the railway station and to take only 15 kilos of luggage with them. They were mostly women, children and old people. They were supposed to be gone for four weeks, but it ended up being four years.

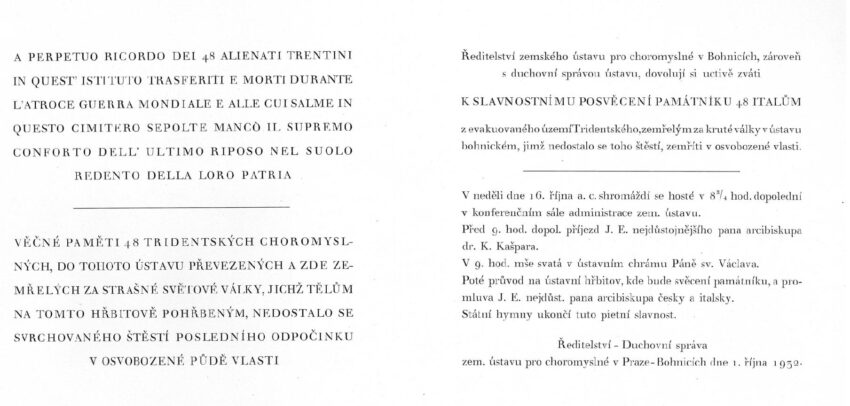

So, in the cemetery of Bohnice, 48 Italian refugees are also dreaming their eternal dream here, -patients (total number of Italian patients 281) who were mostly sickly.

Italy did not forget them and in 1932 a memorial plaque was installed here, paid for personally by Benito Mussolini and unveiled by Ambassador Quido Rocco. The commemorative plaques, which were bilingual, were consecrated by Archbishop Kašpar, and on 16 September a long procession of inmates and local villagers marched from the institute, a glory that went beyond the borders of Czechoslovakia, and this commemorative ceremony was reported not only in our newspapers but also in Italian ones. Today the memorial plaque does not exist and you would be hard pressed to find its place. Only on the chapel you can see a small iron box at the bottom in which soil from his native Pergier was placed.

This June, I handed over to the Italian side all the names of the Italian dead, which I have compiled thanks to the book of the deceased and partial research in the cemetery. Perhaps this also brought to a close a sad chapter of the Great War, which brought these sad human fates from far-off Pergia to us in Italy.